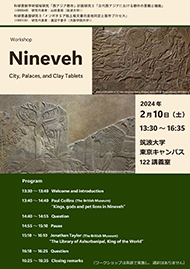

Workshop: Nineveh: City, Palaces, and Clay Tablets

科研費新学術領域研究「都市文明の本質」(代表:山田重郎)および科研費基盤B「メソポタミア粘土板文書の産地同定と製作プロセス」(代表:渡辺千香子)による講演会を開催します。

〈日時〉 2024年2月10日(土) 13:30-16:35

〈会場〉筑波大学東京キャンパス122講義室 (地下鉄丸ノ内線茗荷谷駅から徒歩3分)

〈プログラム〉

13:30~13:40

Welcome and introduction

13:40~14:40

Paul Collins (The British Museum), “Kings, gods and pet lions in Nineveh”

14:40~14:55

Question

14:55~15:10 Pause

15:10~16:10

Jonathan Taylor (The British Museum), “The Library of Ashurbanipal, King of the World”

16:10~16:25

Question

16:25~16:35

Closing remarks

(ワークショップは英語で実施し、通訳はありません)

Abstracts:

Paul Collins: Kings, gods and pet lions in Nineveh

The carved relief panels that lined palace walls in Nineveh served to not only record the king’s triumphs over rebellious people and dangerous animals but, it will be argued, also actively participated within rituals of kingship that evoked the agency of the gods. Text and images worked together to establish a relationship between the monarch and a mythical past and a perfect future, thereby ensuring Assyrian kingship was timeless. Among the most celebrated of these sculptures and associated texts are depictions of King Ashurbanipal (668-about 630 BC) killing a succession of fierce lions. As well as scenes of slaughter, however, a few surviving relief panels depict what appear to be tame lions in a very different setting; their meaning can be understood in the context of the close connections between the royal family and their gods.

Jonathan Taylor: The Library of Ashurbanipal, King of the World

The “Library” of Ashurbanipal, 7th century BC King of Assyria (northern Iraq), is one of the most important archaeological discoveries ever made. It forms the central pillar of Assyriology. Ashurbanipal combined supreme power―ruling an empire spanning ancient western Asia―with a hunger for knowledge. This scholar king assembled what seems to have been a complete collection of the scholarship known in his day. His library was destroyed in 612 BC, surviving to us in the form of 30,000 fragments of clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform texts. In the 170 years since its discovery, scholars have learned much about individual books once held in the library. Yet the library itself remains poorly understood. New research sheds important light on the royal collection. How many books were in it? How was it put together? And how did the Library change over time?